Hands are not only infinitely useful for basic survival, like grabbing our dinner - they also serve as signals in social situations.

People twiddle their thumbs. Tap the table nervously. Give a thumbs up - or “the finger”. They rest their weary head in their hands, or clasp it in despair.

Imagine Rodin’s thinker without hands: impossible.

Rodin’s Thinker, The Louvre, photograph by AndrewHorne, source: Wikipedia

Similarly, in Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” above, the elongated hands are essential in amplifying despair.

Our hands give us away - they show who we love, loathe, muse; how we feel (jittery or relaxed). That’s why we love holding stuff in our hands, whether it be a cigarette or mobile phone. It makes it harder to ‘read’ us, to know that we’re terrified or maybe head over heels in love with the person sitting next to us.

“Hangover - the Drinker” - Portrait of Suzanne Valadon, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec 1887-88 - Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge

In most portraits, the hands have something to do or rest on: people who aren’t actors simply don’t know what to do with them otherwise.

The brilliant photographer Irving Penn was very well aware of this. In most of his portraits, the sitters’ hands are given something to do.

We see Salvador Dali, legs wide spread, holding his knees.

There’s Jean Cocteau managing to very elegantly have a hand in his pocket, whilst holding a cigarette in the other.

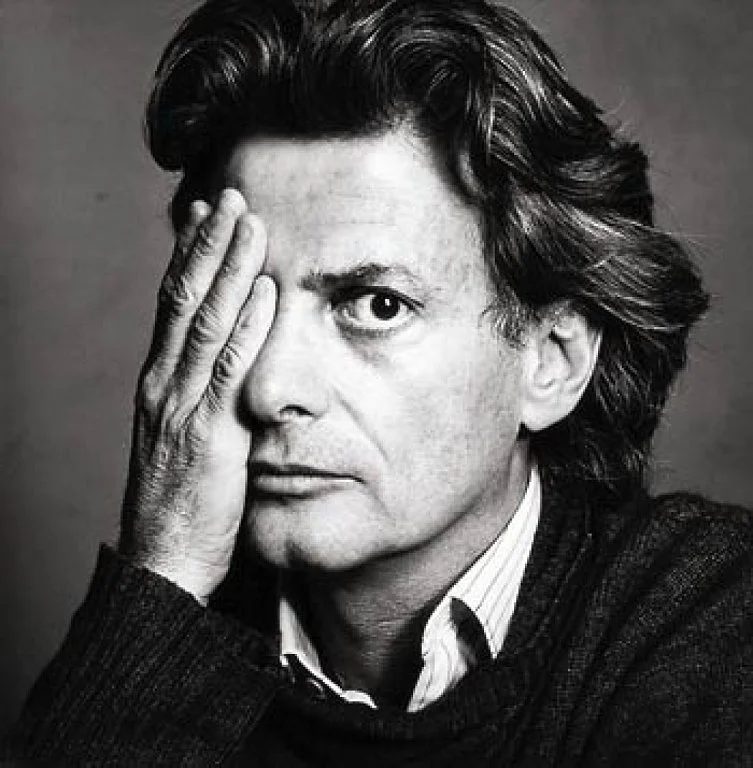

Richard Avedon covering his face with his hand, leaving a gap for his all-important photographer’s eye.

And Penn’s portrait of Miles Davis leave out the face entirely in favour of the all-telling hand: all we see is Davis’ , pressing an imaginary valve on a trumpet.

Today, observe how people use their hands - and how artist use depiction of hands to express how their subjects feel.

See how their hands tell stories - whether they want to share them or not.

Share your hands that speak volumes on Twitter or Instagram, using the hashtag #kramerseye.