I hope this week has given you a new appreciation for two incredible tools you use daily: your hands - and how they’re used in art to give direction and meaning.

If you’d like to dive deeper into this fascinating topic here are some suggestions for weekend projects.

Looking at art

Observe how hand depiction has changed through periods, for example the Middle Ages. grab screenshots and create your own ‘Medieval Art Hand’ timeline.

(Re)visit a museum or online art collection and focus on hands doing a particular thing. For example pointing, blessing, praying - or holding a particular object, like a sword. Again, take pictures or screenshots to create your own mini collection (the Rijksstudio, one of my favourite online art resources, has this function built-in).

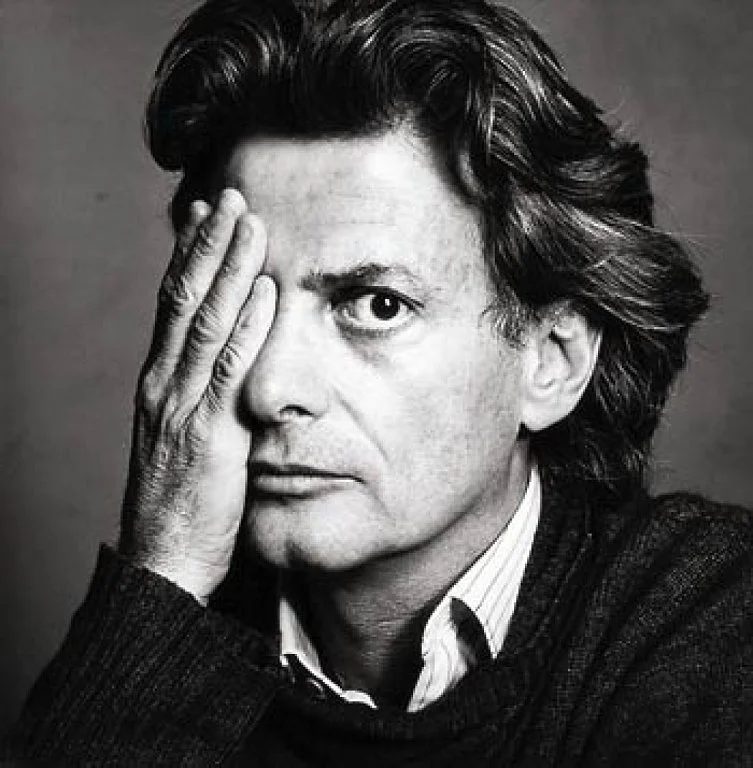

Look at how some of your favourite artists, photographer or others, treat hands. Do they play an important part in their pictures?

Look at studies of hands by different artists and marvel at how many shapes they can take and how hard it is to draw or paint them well

Cheers! Detail of A Militiaman Holding a Berkemeyer, Known as the ‘Merry Drinker’, Frans Hals, c. 1628 - c. 1630, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Creating your own work

Revisit Tim Booth’s hand project and think about the important people in your life. How would you portray them through their hands? This can be a great start of a new photography project - as well as an interesting conversation to have with those close to you. How do they see themselves? And what does this mean about how they would like to be portrayed through their hands?

At the start of this week we looked at how hand prints say ‘I was here’. But there’s another much loved visual theme which says ‘Someone was here’: lost gloves. From now on, keep your eye out for lost gloves and start creating your own collection.

Zoom in on hands through macro photography. Create close-ups of hand palms and make visible what amazing landscapes they are. You can even consider superimpose portraits of the palm-owners on these for a double-layered portrait.

There’s lots more to be observed and created around this amazing topic, so we may very well revisit it later on. But this should give you plenty to do for now.

Have fun with hands this weekend and do share your creations on Twitter or Instagram, using the hashtag #kramerseye.